Bohème Secrets

You love Bohème and you know that Puccini achieved something exceptional with his score. The success and endearment of this opera is so overwhelming however, that we might be blinded to some relevant factors. Here are some unjustly forgotten facts, or as I like to call them: Bohème Secrets

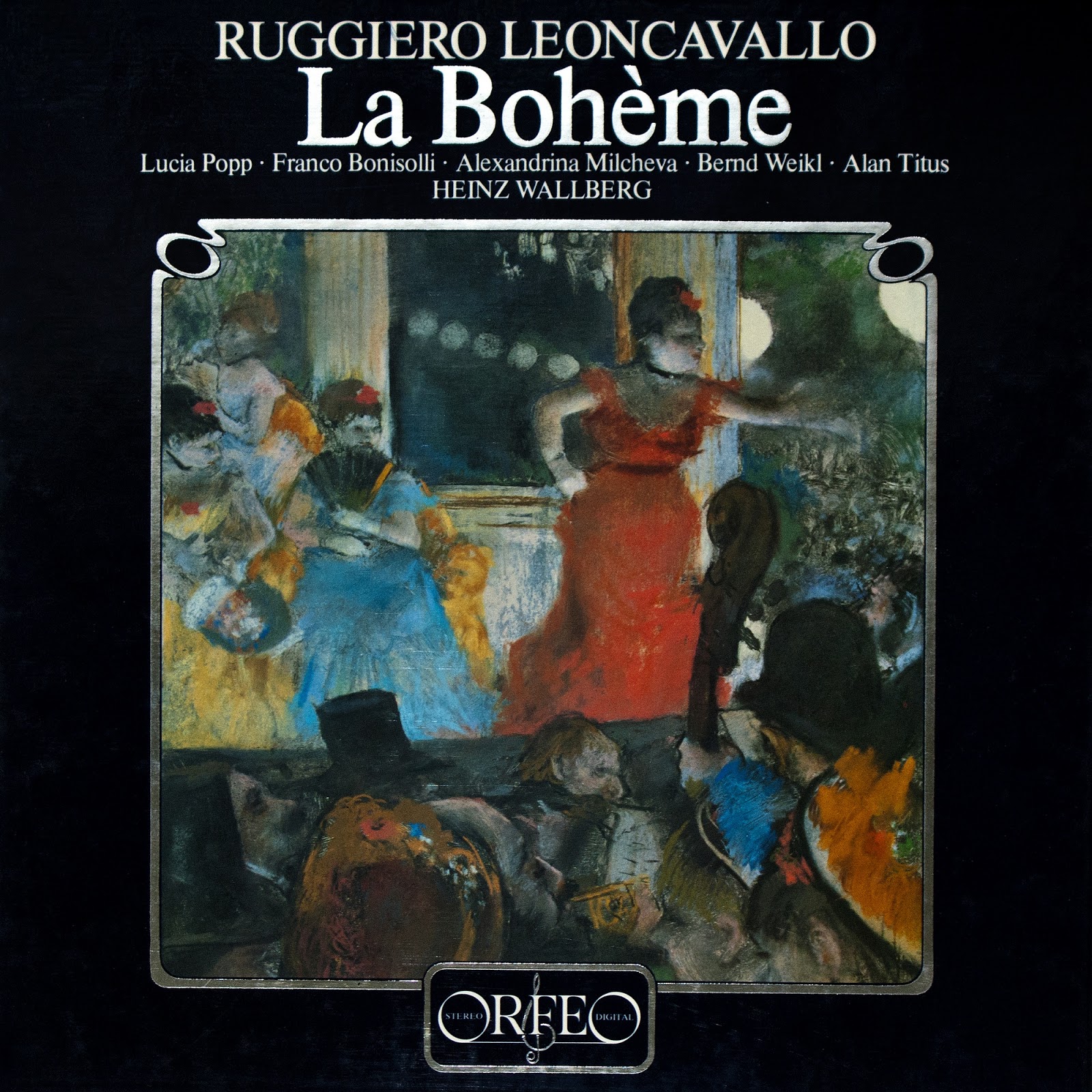

Ruggero Leoncavallo stated that he first ever came up with the idea of composing an opera based on 'Scénes de la vie de bohème' by Henry Murger. In fact, he even claimed to have asked Puccini whether he could be interested in doing that, but Puccini hadn’t shown interest, as he was then on the look out for a verismo subject (‘La lupa’). Leoncavallo went on to compose his 'La bohème', only to find out a year later that Puccini ALSO started to compose his own Bohème. Both composers were upset with each other, but persisted with their ambitions. Puccini's premiered first in Turin; Leoncavallo’s a year later, in Venice. I am tempted to believe that had Puccini not written his extraordinary Bohème, Leoncavallo's would have remained in the repertoire, for it is a good piece, full of the charm and passion of Murger's young characters and supported with moments of musical flight and drama. Listen for example to the following audio file: Schaunard sings a song “On the influence of blue on the arts”, accompanying himself at the piano during a party given by Musette. His concert causes the neighbors to complain about the ‘noise’, but he carries on even more enthusiastically with a Rossini parody put to excellent comical effect.

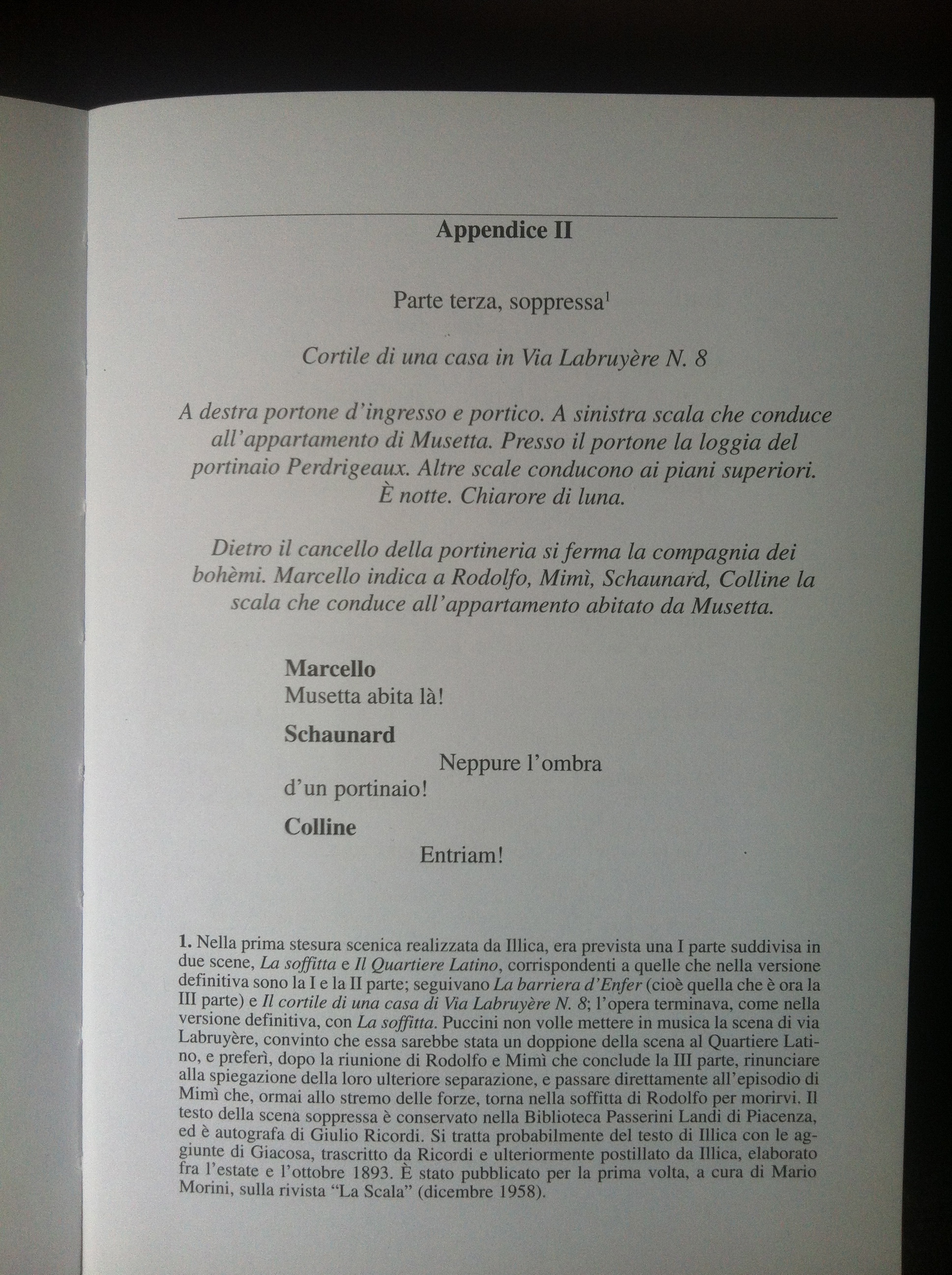

The original scenario for La bohème included 5 acts. There is one other act that was intended to go in between the now 3rd and 4th acts. This scene had been worked out in complete detail by the authors: Giuseppe Giacosa and Luigi Illica. Yet, to their dismay, Puccini decided not to compose it, and proceeded directly to the last act. His reason was that the material for this act would have required another comical ensemble like the one he composed for the 2nd act, and that even if he could write something as good as that, it risked being an imitation. We respect his instinct, but we should also remember the righteous frustration of the writers, because their dramaturgy lost coherence.

The 'fifth' act takes place at Musetta's apartment building. She had been living in comfort paid by her benefactor, but now that the relation is over, the rent is not paid any more, and she has to move out. As the act starts, it is evening and the movers are busy taking the furniture down, and she is informed that she has until dawn of the day after to return the keys. Half frustrated and half emboldened by the new freedom, she decides to throw a party, right at the building's courtyard where all the furniture is being gathered for moving in the morning. She invites all her friends and the neighbors. Also present at the party is the Visconte Paolo ('un moscardino di viscontino'), who dances with Mimì. When Rodolfo notices that Mimì is dancing with another, he causes a scene of jealousy by accusing her, which everyone is quick to restrain. Mimì goes on dancing with the Visconte, and Rodolfo observes in frustration, which occasions him to get drunk and sing tragically about the end of love, while the ensemble rages on in tragicomic contrast through the night, in turns of group singing, dancing, and movers at dawn. What an act this would have been!

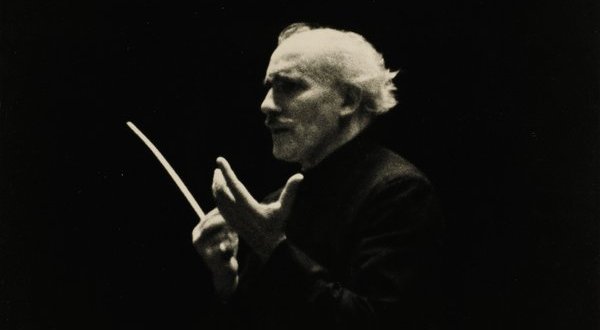

Arturo Toscanini conducted the premiere of Boheme in 1896. Fifty years later, he conducted a live broadcast with the NBC Symphony Orchestra, in 1946. The recording of this event, now available in CD format, is one of the most fascinating documents regarding the interpretation of Boheme, and of Puccini in general. Listening to it, one has the impression of a highly disciplined reading of the piece. Surely, the fact that they were all standing with the music in front of them and the maestro in full display has something to do with this strict reading. But one knows that Toscanini's stage performances were full of breath and flexibility (listen for example to the recording made of a live performance of 'Falstaff' in Salzburg, in 1932). This Bohème, strictness aside, is full of coherence, and is impassioned yet not sentimental. The singers sound like the characters they portray: young and impulsive. Especially Licia Albanese as Mimì, a lighter soprano singing this role, comes as a revelation. Toscanini was 78 years old, but he also sounds young and inevitable with his blazing energy and drive. Here is Mimì's aria from the 3rd Act.

During the many productions of Bohème that took place in Italy during Puccini's lifetime, he was known to attend rehearsals, giving notes and advice to everyone. Present as a pianist and assistant was maestro Luigi Ricci. He was assistant conductor at Teatro dell’Opera di Roma, and in that capacity he helped Puccini rehearse his operas during 8 years. Ricci had a habit of notating Puccini's remarks in his vocal scores, which produced an admirable compilation of commentary and explanation. He then wrote down a book, giving account to this wealth of information: 'Puccini, interprete di se stesso' Ricordi, 1954. After reading these pages, one understands the origin of so many performance traditions, interpretations that didn't make it to the printed score, but are known to singers and conductors from famous vintage recordings, and oral traditions. Ricci himself coached a generation of famous singers. Here is my favorite quote, from Puccini to a conductor: “Vita! Vita, Maestro! Se s’addormenta lei, ci addormentiamo tutti!” (“Life!, Life, Maestro! If you fall asleep, we all fall asleep!”).

One aspect of this book deserves special mention: portamento. Puccini loved and encouraged the use of portamento, which is a form of slow binding between two notes, producing anything from a gentle slide to a torrent of flowing sound. This is an art that became outmoded in the second half of the 20th century and is still largely disregarded by many. Yet, that was the way they played and singed during Puccini's lifetime, and he advocated for it. Listen for example to this extraordinary 1938 recording by Beniamino Gigli (a personal friend of Maestro Ricci), with the orchestra of La Scala, conducted by Berrettoni.

Have you ever wondered about the use of the words 'Lorito' and 'Lulù' in La Bohème's libretto? What do they mean? Why did Illica and Giacosa use these words? I figured this out by chance during a visit I made to "Museo Villa Verdi - Sant'Agata di Villanova" in Parma, Verdi's house. Wondering around in the several rooms open to visitors, noticing how everything has been kept as it was in Verdi's last days: from the books on the shelves, the positioning of furniture, the objects on the desk, to the art on the walls, everything is exactly as Verdi left it when he died. The impression is endearing and moving. And then there is a surprise: in one wall, there are two oval portraits of what were Verdi's house pets: a parrot and a dog, Verdi loved them so much that he had an artist paint their likenesses, kept in loving memory after the creatures died their natural deaths. This is what the Bohème authors used to salute their beloved old Maestro, by referreing to his pets: for their names were LORITO, the parrot, and LULU, the dog!!!